Cosmetic surgery is often an art form, occasionally a necessity, and sometimes even a private obsession. As a result, it’s tricky to sort out what to do when you’re dissatisfied with your results, and where the blame lies.

Consider this: As exaggerated looks fall out of fashion, plastic surgery reversals are on the rise. People that went under the knife to achieve their perfect “Instagram Face” now want a more natural appearance. Others seek to reverse once-trendy cosmetic enhancements like fox eye thread lifts, ski slope noses, and even Brazilian butt lifts. Sadly, most invasive cosmetic procedures can’t easily be reversed.

What about surgeries that leave patients unhappy from the get-go? Here the issues are murkier.

I’m going to guide you through the tricky challenge working with your surgeon when you’re not thrilled with your cosmetic results. But first, here are steps you should take if you are dissatisfied in any way.

- Take well lighted photographs of your results on a regular basis as you’re healing.

- Make an appointment to see your surgeon.

- Document your communication with your surgeon’s office via contemporaneous, written notes. Consider recording your phone calls and post-op visits, too (you’ll need permission in certain states that require two-party consent).

- Seek a second opinion from a surgeon that specializes in the type of surgery you had.

In my experience, patient dissatisfaction usually results from one of the following problems:

- The surgeon doesn’t carefully manage patient expectations or explain risks or fails to screen out patients that are unfit for cosmetic surgery.

- The patient blames the surgeon for irregularities that sometimes occur during the healing process or loses patience with a lengthy healing time.

- The surgeon botches the surgery by being overly aggressive or otherwise inept at producing the patient’s desired aesthetic result.

- The patient experiences serious complications requiring surgical repair.

Now let’s explore each of these problems in reverse order.

Serious Complications

Bad plastic surgery fascinates us. There are entire websites devoted to exposing before-and-after calamities, and some celebrities have even found the courage to “out” themselves after poor results. But there’s a big difference between unsatisfactory aesthetic outcomes and medical complications requiring immediate attention.

Medical Complications

Medical complications are no joke, and can leave patients with permanent pain, paralysis, and disfigurement. I’ve seen patients lose nipples and the tips of their noses, suffer drooping eyelids, and even become blinded by simple filler procedures.

Though generally safe, complications can occur even in the best of hands. Hematoma and bruises, seroma formation, nerve damage causing sensory or motor loss, infection, scarring, blood loss and complications of anesthesia can occur in any surgery. More serious complications such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism can cause death.

Khunger N. Complications in Cosmetic Surgery: A Time to Reflect and Review and not Sweep Them Under the Carpet. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8(4):189-90. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.172188 (link)

Medical complications usually show up shortly after surgery, and your surgeon is obligated to do everything they can to help you free of charge. But you have to make a quick decision whether to allow your original surgeon to take corrective action, or seek a different surgeon that will charge you for their work.

Many people quickly dismiss their original surgeon out of frustration, but the fact is that your original surgeon, by knowing how you heal, and how your surgery turned out, may be in the best place to make sure corrective surgery is effective.

Kita, Natalie (1 June 2022). What to Do If Bad Plastic Surgery Happens to You. Retrieved from verywellhealth.com (link)

Aesthetic Complications

Unsatisfactory aesthetic results don’t cause physical harm but are often emotionally traumatizing. These typically result from surgeons being overly aggressive. With liposuction this can lead to skin dimpling, and with facelifts, an overly tight look. I’m even aware of cosmetic surgeons that decided to up-size breast implants while their patients were asleep in the table.

Unlike with a medical complication, if you’re desperately unhappy with your aesthetic result and believe your surgeon botched your surgery, you’re likely to face a challenge convincing them to address your aesthetic concerns free of charge. Upstanding practitioners will try working with you one way or another. But the devious ones will attempt to run out the clock on the one-year statute of limitations for filing a lawsuit against them by treating you with fillers and light energy devices, then throw up their hands and tell you they can’t help you any longer.

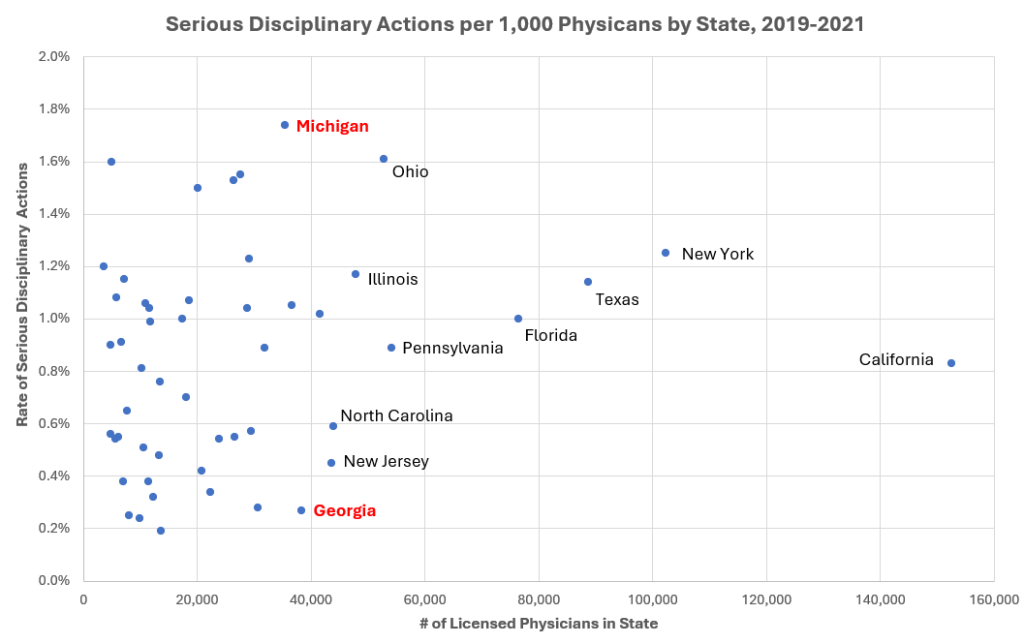

If you experience a serious issue — whether medical complication or botched aesthetic result — you should consider seeking help from a mental health professional, as disfiguring injuries can be psychologically devastating. If you believe your problem resulted from a surgical error, pull together your documentation and file a complaint with your state medical board (click here to access state-by-state contact information). If you wish to file a lawsuit seeking financial damages from your surgeon, be aware that this will be a frustrating and time-consuming process, so make sure you’re up to it, as cases like these can be surprisingly difficult to prove.

Minor Irregularities

This grey zone is a much tricker one to navigate, in part because the healing process can sometimes stretch out 6 to 12 months (and up to 24 months for some nasal procedures). If your surgeon asks you to wait and see, a little voice in your head might be telling you that your healing process is not normal, and something is wrong. What to do?

“After a nose job, your nose isn’t REALLY healed until two years after the fact. You might love it initially, but it will change during that time, and there’s a high chance you won’t like it after it’s healed. My nose job was great until it actually healed. Now it’s crooked and obviously collapsing on one side from the surgeon removing too much.”

Herenda, Devin (26 Aug 2022). People Who Have Had Plastic Surgery Are Sharing Their Stories, And the Comments Will Totally Change Your Perspective on the Subject. Retrieved from BuzzFeed.com (link)

In my decades of experience, despite what your surgeon might say, irregularities that appear early in the healing phase sometimes don’t resolve satisfactorily. For instance, if a patient has poor skin tone, their facelift might begin sagging again only months after surgery, or dents or ripples might appear. Breast implants may encapsulate at any point, requiring a revision procedure. For rhinoplasty patients, over time their noses can become crooked months or years later as the cartilage slowly heals. And some patients experience excessive scarring for no reason at all.

In cases like these where the surgeon likely didn’t do anything wrong, it’s their call about whether and how to address your concerns. Some surgeons will agree to perform a free revision and only charge you for their “hard costs” (anesthesia and operating room time). Others will avoid you, hoping you’ll go away. Still others will tell you that they don’t feel confident addressing your concerns and refer you to a different doctor.

If your surgeon is dragging their feet, your best recourse is to seek a second opinion to help you determine if your concerns result from surgical error, are simply part of a normal healing process, or just bad luck.

Mismatches Between Patient Expectations and Surgical Results

In cosmetic surgery, unrealistic patient expectations are never a good thing. These can result from communication errors on the surgeon’s part, or from patients that aren’t psychologically fit and might suffer from obsessive compulsive disorder or body dysmorphic disorder.

Communication errors. To reduce the chance of a mismatch between your expectations and your surgical result, sit with your surgeon and review before-and-after pictures from other patients until you find the precise “look” that you’re after. Communication errors also occur during the surgical consent process, when surgeons are supposed to explain the risks and potential complications of your procedure in language a layperson can understand. For instance, I recently consulted for a patient that suffered a catastrophic complication called empty nose syndrome after her nasal turbinates were removed by a cosmetic surgeon during a rhinoplasty. She claimed her surgeon never informed her of the risk of this syndrome or properly consented her for this irreversible procedure, and they are now in litigation.

Patient psychology and lifestyle. Even when surgeons are crystal clear about the risks and limitations, some patients are simply unrealistic about what cosmetic surgery can achieve, or have psychological or lifestyle risks that make them unfit for such procedures. For instance, after a liposuction procedure, it’s common for overweight people to complain that the surgeon didn’t remove enough fat, even after being told that taking any more would have been unsafe. Naturally, patients that smoke or abuse drugs or alcohol might be poor candidates for certain types of procedures. Before you undergo cosmetic surgery, be honest with yourself about whether you’re a good candidate and are resilient enough to handle imperfect results. After your surgery, if you’re fixated on imperfections, try insisting that your surgeon do something to help you, and consider working with a friend or maybe even a therapist to explore your concerns.

People with body dysmorphic disorder may still have true bad surgical outcomes just as anyone else, and it can be helpful to have a therapist help make the distinction.

Kita, Natalie (1 June 2022). What to Do If Bad Plastic Surgery Happens to You. Retrieved from verywellhealth.com (link)

Takeaways

If nothing else, I hope this article helped you appreciate how important it is to do your homework before undergoing any elective surgical procedure. Take your time evaluating prospective surgeons, read and understand everything in your surgical consent form, and take responsibility for your decisions and healing process. For tips on all these subjects, click over to my companion articles:

Trying to evaluate surgeons for your elective procedure? Good luck! (link)

So, you’re having elective cosmetic surgery? Keep an eye on your surgical consent form. (link)

You need to care about your aftercare (link)

Nothing in this article should be relied on for medical or legal advice.

Copyright © 2025 by Monica Berlin